An unmet need persists in the management of Parkinson's disease (PD)

The progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in PD leads to profound declines in daily functioning and a significant loss of quality of life1,2

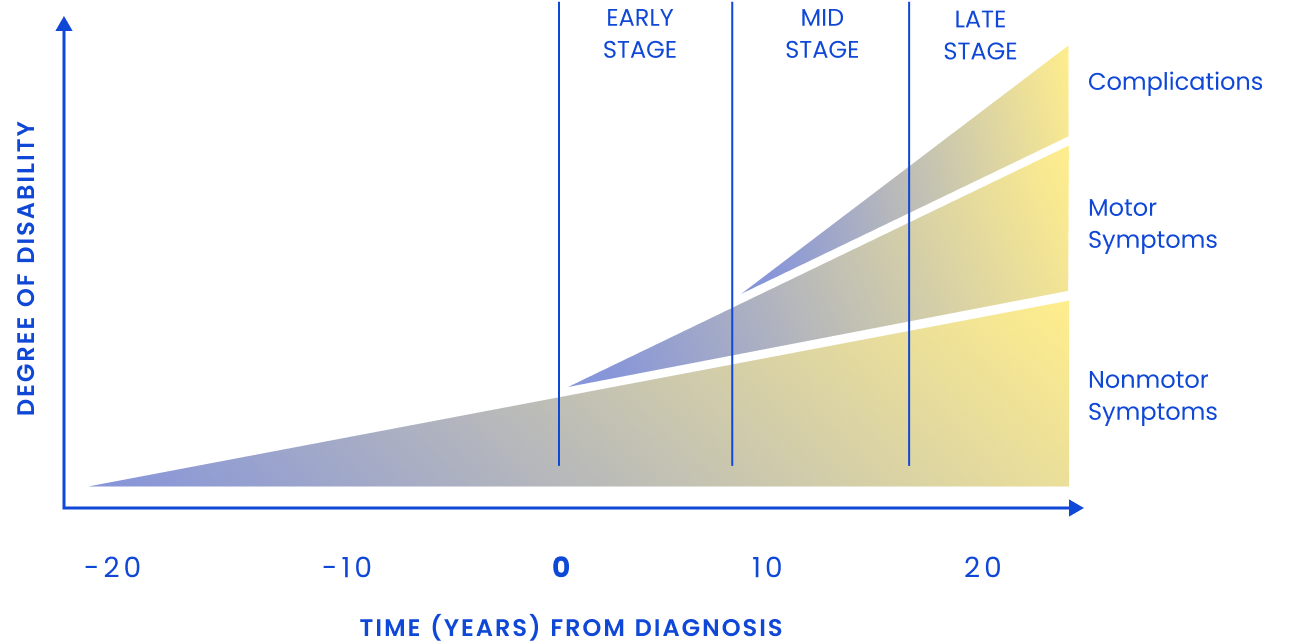

PD Trajectory: Time Course of Motor and Nonmotor Symptoms Progression3

Nonmotor symptoms can appear over a decade before motor signs, including GI dysfunction, sleep disturbances, hyposmia (loss of smell), and mood changes3

By the time motor symptoms appear, approximately 50% of dopaminergic neurons are lost and up to 80% of striatal dopamine has been depleted4-6

As PD progresses, patients commonly experience3:

Motor fluctuations and dyskinesia

Dysphagia

Dementia and psychosis

Postural instability and falls

Freezing of gait

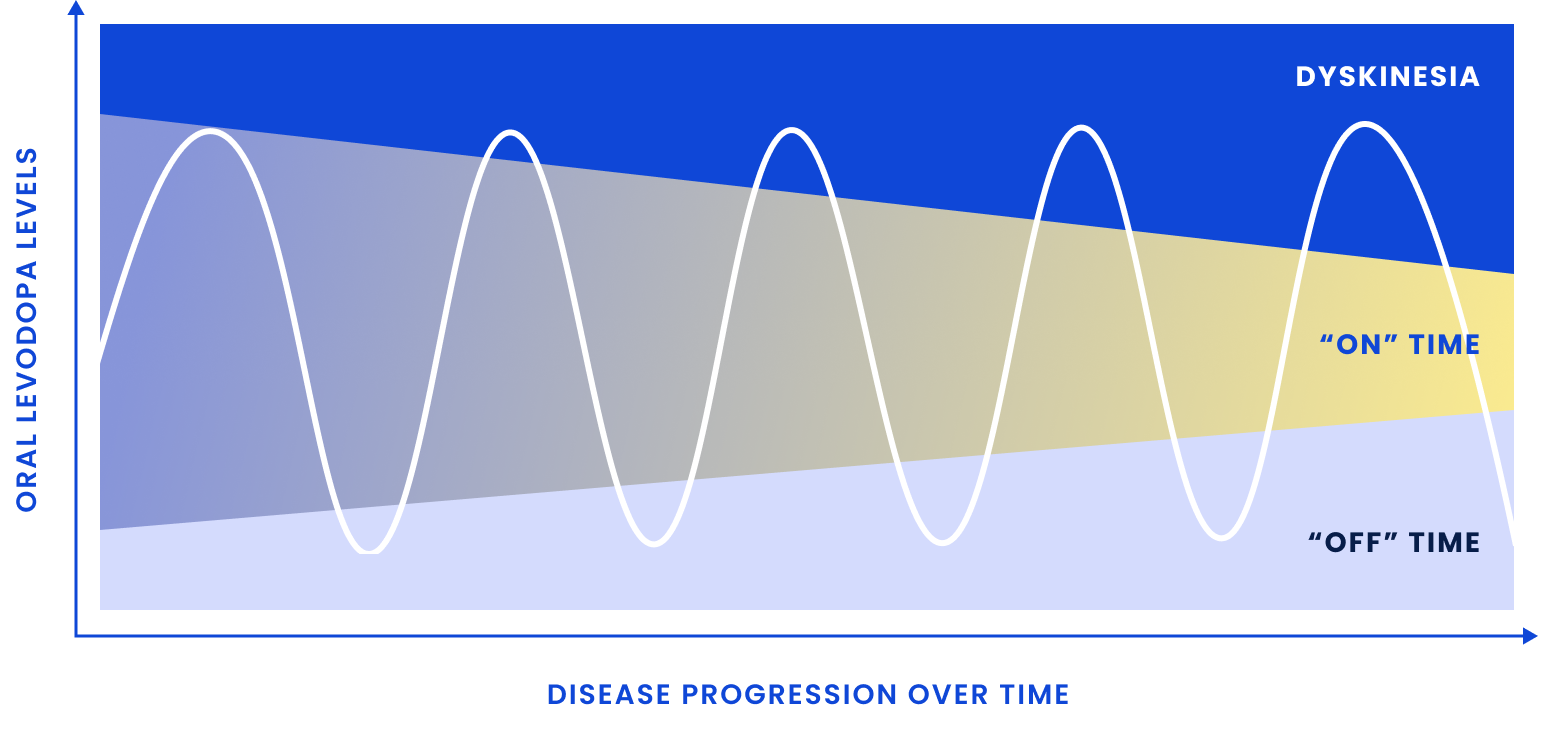

As the therapeutic window narrows, treating symptoms becomes more difficult, creating additional burden for patients7-10

Patients may require

more frequent and/or higher doses of oral carbidopa/levodopa (CD/LD) to address wearing off due to the short half-life

Patients may experience

an increase in dyskinesia and other adverse effects related to treatment

See how dopamine receptor subtypes work in different ways and review their relevance in PD

GI=gastrointestinal.

References: 1. Kouli A, Torsney KM, Kuan WL. Parkinson's disease: etiology, neuropathology, and pathogenesis. In: Stoker TB, Greenland JC, eds. Parkinson's Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects. Codon Publications;2018:3-26. 2. Váradi C. Clinical features of Parkinson's disease: the evolution of critical symptoms. Biology (Basel). 2020;9(5):103. doi:10.3390/biology9050103 3. Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2015;386(9996):896-912. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3 4. Ravenhill SM, Evans AH, Crewther SG. Escalating bi-directional feedback loops between proinflammatory microglia and mitochondria in ageing and post-diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(5):1117. doi:10.3390/antiox12051117 5. Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(5):2283-2301. doi:10.1093/brain/114.5.2283 6. Chen H, Burton EA, Ross GW. Research on the premotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: clinical and etiological implications. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:1245-1252. doi:10.1289/ehp.1306967 7. Boelens Keun JT, Arnoldussen IA, Vriend C, van de Rest O. Dietary approaches to improve efficacy and control side effects of levodopa therapy in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2021;12(6):2265-2287. doi:10.1093/advances/nmab060 8. Antonini A, Moro E, Godeiro C, Reichmann H. Medical and surgical management of advanced Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2018;33(6):900-908. doi:10.1002/mds.27340 9. Ellis JM, Fell MJ. Current approaches to the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27(18):4247-4255. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.07.075 10. Poewe W, Mahlknecht P. Pharmacologic treatment of motor symptoms associated with Parkinson disease. Neurol Clin. 2020;38(2):255-267. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.12.002