Dopamine receptor pathophysiology in Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by progressive and debilitating motor symptoms, which are the hallmarks of the disease and a major focus of current therapeutic intervention.1-4 Although Parkinson's disease is typically diagnosed when motor symptoms are present, the disease process usually begins before these symptoms occur.4 People living with Parkinson's disease also experience nonmotor symptoms.5

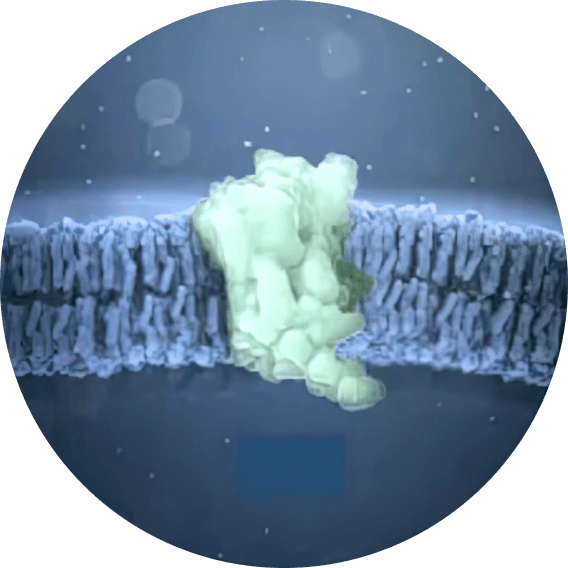

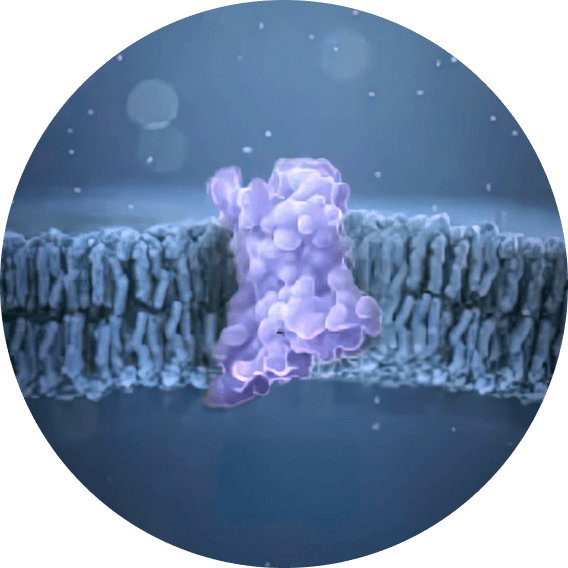

In Parkinson's disease, dopamine is the most disrupted neurotransmitter and acts through multiple pathways in the human brain.6,7 Let's look more into a few of these pathways in healthy conditions. One major pathway is the nigrostriatal pathway, which is involved with motor control.7 Other key pathways are the mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways, in which different areas containing dopamine neurons play a role in reward and cognition, respectively.7,8 Within the pathways there are 5 different receptor subtypes through which dopamine signaling can occur.9 D2, D3, and D4 dopamine receptors are referred to as D2-like receptors.2,10-12 These receptor subtypes are the primary targets of currently approved dopamine agonists.2 The other two dopamine receptors, D1 and D5, are referred to as D1-like receptors.2,10-12 Within the nigrostriatal pathway in Parkinson's disease dopamine-producing neurons degenerate in the substantia nigra, leading to a loss of dopamine signaling and the emergence of motor symptoms.3,13-14 Treatment focuses on offsetting the effects of these degenerating neurons by restoring dopamine signaling to improve some of the motor symptoms.2,3,7 Now let's review some of the current treatment options.

Levodopa, which is a dopamine precursor that gets converted into dopamine, is the current oral standard-of-care for Parkinson's disease.10,15 It leads to the activation of all dopamine receptors along the dopamine pathways.2,10,15 Over time, neuronal degeneration, neuronal death, and pulsatile stimulation of receptors can lead to unpredictable symptom control with increased dyskinesia.6,15-18 Other currently approved therapies include dopamine agonists, which target the D2 receptor subfamily, primarily at the D2 and D3 receptors.2,15 However, D2/D3 agonists activate receptors that are located throughout many parts of the brain including areas outside of the nigrostriatal pathway that may not be degenerated.2,15 This wide activation of D2/D3 receptors is primarily associated with potential burdensome nonmotor side effects, such as hallucinations, impulse control disorders, orthostatic hypotension, and excessive daytime sleepiness.2,15 These symptoms may contribute to the emotional and physical burden of Parkinson's disease.19 Given that current treatment options may activate off-target dopamine receptors along a wide array of dopamine pathways, a more selective approach could be evaluated.2,10,12,15 For instance, selectively targeting D1/D5 receptors through agonists is a potential approach in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.20,21 A targeted approach to dopamine signaling may be achieved by selective D1/D5 dopamine receptor agonism.20,21 This selective D1/D5 agonism may avoid D2/D3/D4 receptor agonism.20,21 Selective targeting of D1-like receptors may provide a potential new approach to the treatment of Parkinson's disease.20,21

References:

- Tolosa E, Garrido A, Scholz SW, Poewe W. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(5):385-397. doi:10.1016/S1474- 4422(21)00030-2

- Isaacson SH, Hauser RA, Pahwa R, Gray D, Duvvuri S. Dopamine agonists in Parkinson's disease: Impact of D1-like or D2-like dopamine receptor subtype selectivity and avenues for future treatment. Clin Park Relat Disord. 2023;9:100212. doi:10.1016/j.prdoa.2023.100212

- Hussein A, Guevara CA, Valle PD, Gupta S, Benson DL, Huntley GW. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: the neurobiology of early psychiatric and cognitive dysfunction. The Neuroscientist. 2023;29(1):97-116. doi:10.1177/10738584211011979

- DeMaagd G, Philip A. Parkinson's disease and its management: part 1: disease entity, risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis. P T. 2015;40(8):504-532.

- Fernandes M, Pierantozzi M, Stefani A, et al. Frequency of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's patients with motor fluctuations. Front Neurol. 2021;12:678373. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.678373

- Kouli A, Torsney KM, Kuan WL. Parkinson's disease: etiology, neuropathology, and pathogenesis. In: Parkinson's Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects. Stoker TB, Greenland JC, eds. Codon Publications; 2018. Accessed January 28, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536722/

- Choi J, Horner KA. Dopamine agonists. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed January 28, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551686/

- Ledonne A, Mercuri NB. Current concepts on the physiopathological relevance of dopaminergic receptors. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:27. doi:10.3389/fncel.2017.00027

- Bhatia A, Lenchner JR, Saadabadi A. Biochemistry, dopamine receptors. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed January 28, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538242/

- Mishra A, Singh S, Shukla S. Physiological and functional basis of dopamine receptors and their role in neurogenesis: possible implication for Parkinson's disease. J Exp Neurosci. 2018;12:1179069518779829. doi:10.1177/1179069518779829

- Reynolds LM, Flores C. Mesocorticolimbic dopamine pathways across adolescence: diversity in development. Front Neural Circuits. 2021;15:735625. doi:10.3389/fncir.2021.735625

- Ayano G. Dopamine: receptors, functions, synthesis, pathways, locations and mental disorders: review of literatures. J Ment Disord Treat. 2016;2(2):1-4. doi:10.4172/2471- 271X.1000120

- Ouerdane Y, Hassaballah MY, Nagah A, et al. Exosomes in Parkinson: revisiting their pathologic role and potential applications. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(1):76. doi:10.3390/ph15010076

- McGregor MM, Nelson AB. Circuit mechanisms of Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2019;101(6):1042-1056. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.004

- Zahoor I, Shafi A, Haq E. Pharmacological treatment of Parkinson's disease. In: Parkinson's Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects. Stoker TB, Greenland JC, eds. Codon Publications; 2018. Accessed January 28, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536726/

- Erekat NS. Apoptosis and its role in Parkinson's disease. In: Parkinson's Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects. Stoker TB, Greenland JC, eds. Codon Publications; 2018. Accessed February 21, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536726/

- Nyholm D. The rationale for continuous dopaminergic stimulation in advanced Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(suppl):S13-S17. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.005

- DeMaagd G, Philip A. Part 2: Introduction to the Pharmacotherapy of Parkinson’s Disease, With a Focus on the Use of Dopaminergic Agents. Pharm Ther. 2015;40(9):590-600.

- Greenland JC, Barker RA. The differential diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. In: Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects. Stoker TB, Greenland JC, eds. Codon Publications; 2018. Accessed February 21, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536726/

- Riesenberg R, Werth J, Zhang Y, Duvvuri S, Gray D. PF-06649751 efficacy and safety in early Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2020;13:1756286420911296. doi:10.1177/1756286420911296

- Sohur US, Gray DL, Duvvuri S, Zhang Y, Thayer K, Feng G. Phase 1 Parkinson’s disease studies show the dopamine D1/D5 agonist PF-06649751 is safe and well tolerated. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2):307-319. doi:10.1007/s40120-018-0114-z